About me

Monet is only an eye, but my God, what an eye! –Paul Cézanne

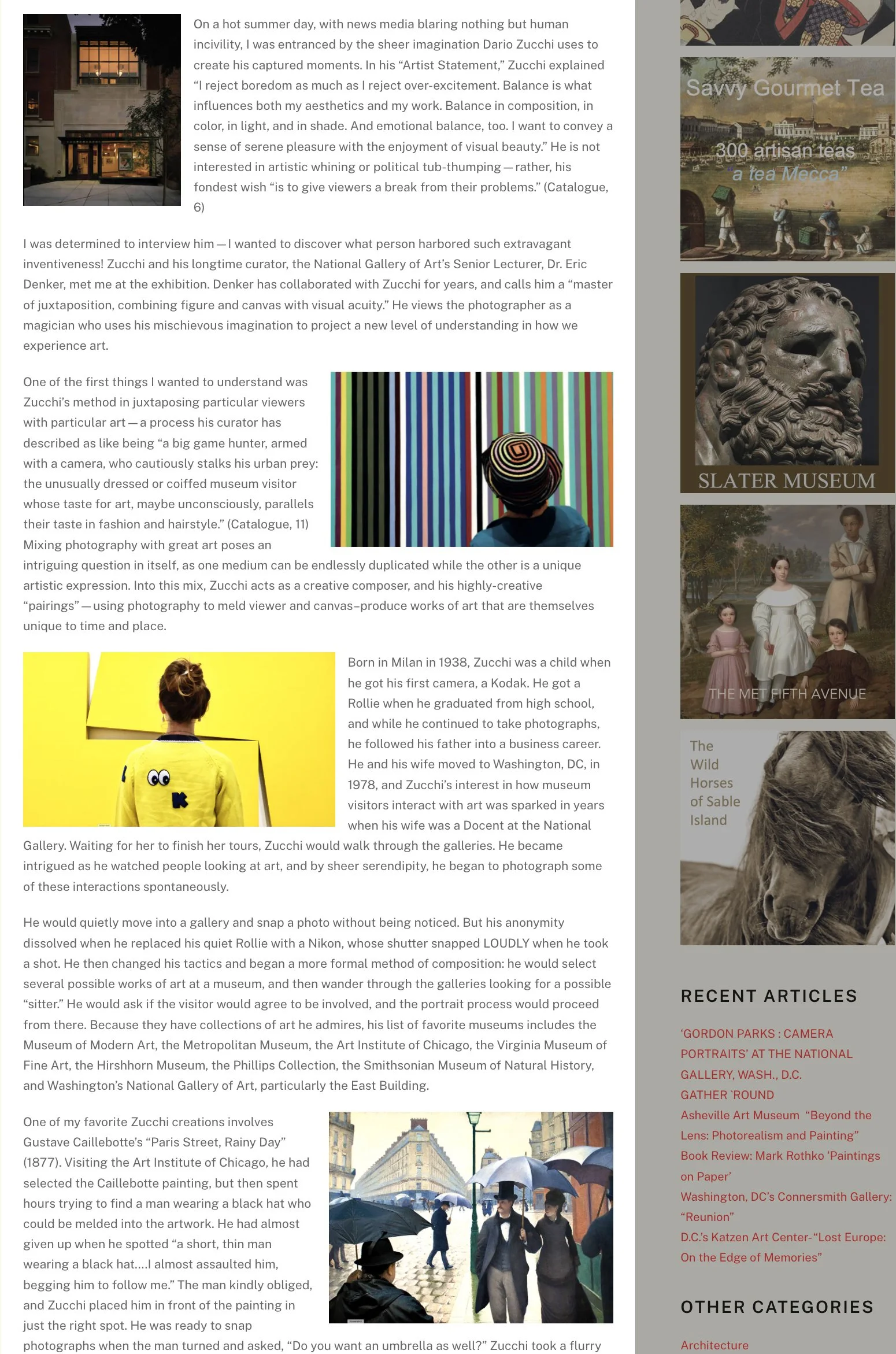

Dario Zucchi also is only an eye, but what an eye. He doesn’t create costumes, construct hats, or construe coiffures. He doesn’t paint or sculpt, or go into the wild to photograph ferocious beasts. He doesn’t go into the darkroom, he doesn’t develop negatives, he’s never manipulated an f-stop. He uses a Nikon D 810 digital camera. Zucchi not only doesn’t use photoshop, he’s never even had it on his computer. He would be the first to tell you that he doesn’t want to be recognized as a technical innovator. Zucchi is a master of juxtaposition, combining figure and canvas with visual acuity. As a photographer he is, at various times, a chef, a magician, an ornithologist, or a lapidary. In his museum photography, with the eye of an experienced jeweler, he selects and cuts the perfect flawless gem for the perfect setting.

Zucchi the Great—the photographer as magician! He exercises his mischievous imagination to conjure brilliant images from otherwise overlooked parallels. He begins with a painting or sculpture or photo that captures his eye. Perhaps we as a casual visitor would have paused, but only for a moment to note a bit of color or errant line. He then identifies a viewer that we may have entirely overlooked save for a quirk in their costume or hair. His photographic sleight-of-hand summons forth an unlikely duet that exists for only one brief startling moment. Abracadabra! The unexpected collision of two charged elements coalesces into a clever new optical juxtaposition.

Wit is a key element in the recipe book of Zucchi’s art. The combination of viewers and art are often insufficient ingredients to produce the artist’s desired confection. A droll cleverness is always an essential ingredient. He seeks what Italians call sprezzatura along with a dollop of surprise. An outstanding Zucchi photograph is as delicate as a soufflé, and like that fragile dessert, something that only briefly exists. Temporality is a key concept in Zucchi’s work. An unassuming visitor wanders in front of an unsuspecting work at an unexpected instance. Voila!

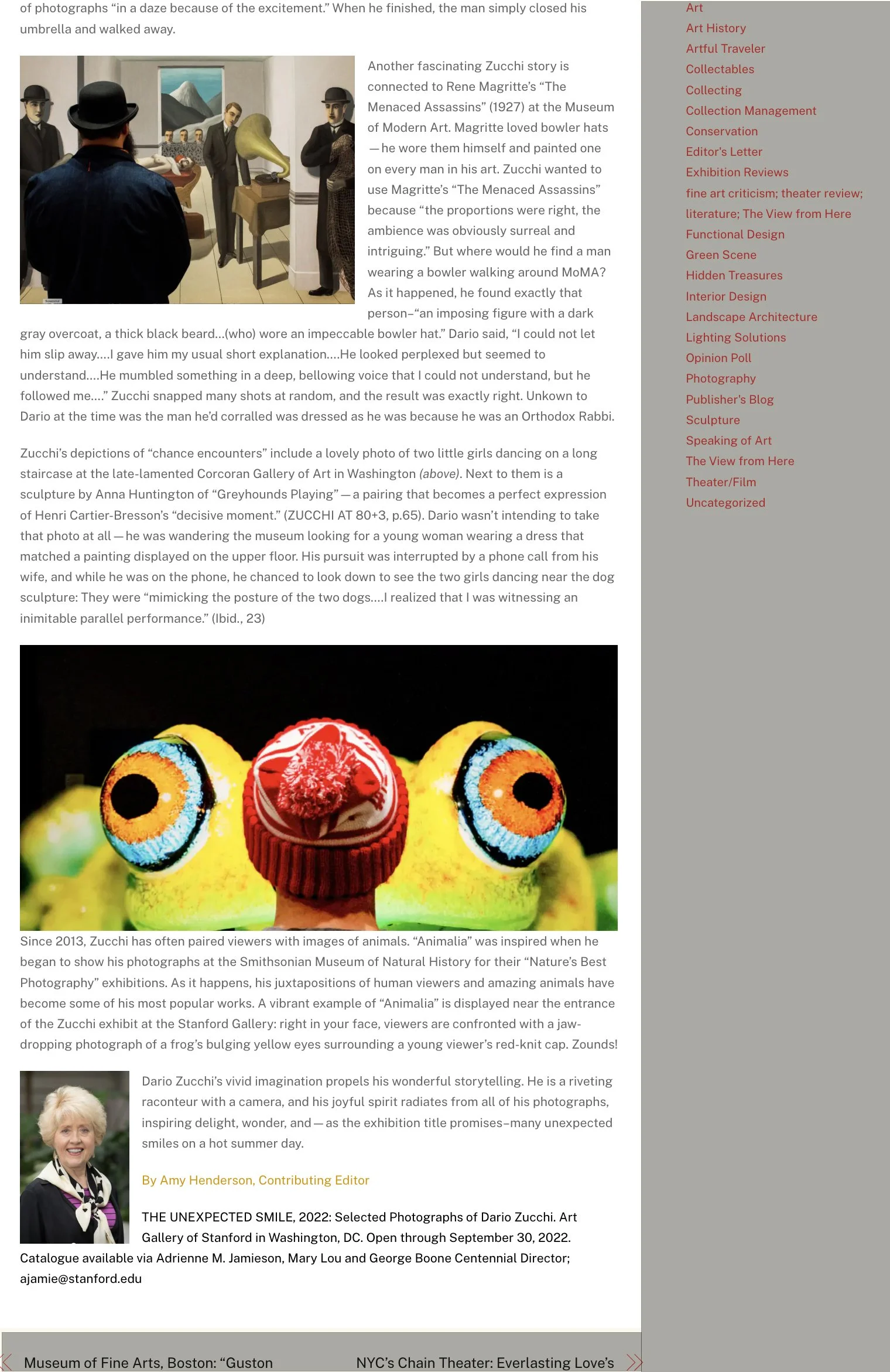

In the last decade Zucchi has embarked on a new direction in his art, the confrontation between museum visitors and large-scale nature photographs. In Animalia the artist moves between the reality of his own photographs and the professional photographer’s monumental images of the animal world.

I am re-immersed in the joyousness of his artistic vision each time I help Zucchi select the photographs for an exhibition. Over the fifteen years we have worked together I have seen many imitators that trade in his approach. Of course, imitation is a form of flattery, even when it is insincere. No one comes close to the level of brilliant improvisation that defines the Zucchi brand.

Dario Zucchi’s photographs reside at the periphery of life and artifice, characterized by humor and a passion for modern and traditional art. The images may be playful, the equivalent of visual puns, but they are also always provocative. As viewers we delight in their novelty as we recognize the clever juxtapositions of painting, sculpture, photography and fashion.

Eric Denker

“Dario’s photos come in the Italian dictionary between sorriso and sorpresa. Sorriso is to smile. Sorpresa, suprise, because thats where the intersection comes.”

Eric Denker

Dario Zucchi and Eric Denker at Strathmore in conversation 2019.

Dario Zucchi at the Italian Embassy in Washington.

An Encounter with Dario Zucchi at the Museum of Natural History

Myers McGarry

The exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, called “Nature’s Best Photography,” explores the 2013 award winners of the Windland Smith Rice International Award, an annual natural photography contest.

My experience in the museum was influenced mostly by the people I saw in the gallery. Along with the countless moms and dads with toddlers, tourists, teenagers and elderly visitors gathered to examine the animals. Many people utilized the “selfie” to incorporate their face into a photograph with the animals. If I was not careful I surely would have bumped into another viewer or tripped over a stroller.

Among the bustle of people an older man with a faint European accent approached me with his camera. I immediately thought that he wanted me to take a picture of him in front of an image. Instead he said, “if you do not mind, I would like to take a photograph of you, but not of your lovely face. Can you stand in front of that kangaroo photograph for me?” I agreed after asking a few questions, posed facing an image of a kangaroo that had an orange background. In the photograph, the animal’s hands crossed the front of its body in an oddly human manner. After the man took the photo, I asked him questions about himself, his work, and what he was going to do with the image of me standing in front of the kangaroo. He said he was originally from Italy but that he and his wife had lived in the district for many years now. Then, he showed me some photographs from his website. Unfortunately, my parking meter was about to expire so I needed to leave, but with the promise that he would hear from me in the next couple of days. It was not until the end of our brief conversation that I learned that his name was Dario Zucchi.

Mr. Zucchi left me with many questions. He seemed kind and unassuming, but quite serious about his work. He was quiet and had appeared from out of nowhere, just as after our talk he disappeared back into the crowd. He enjoyed the exhibition like many others in the room, but he may have stayed there for hours. I studied Mr. Zucchi’s website almost immediately after I returned home to Lexington. On Monday morning I emailed him. He agreed to answer several of my inquiries about the day we met and talked, and about his process as an artist. The relevant parts of our conversation are recorded below with my italicized reflection or elaboration where necessary.

When you saw me what made you think I would pair well with the Kangaroo?

“As I told you when I asked you to move in front of that picture, I never want to take a photograph of the face, I think that that would distract the viewer of my images from “my” work. At first, I was attracted by the sunglasses resting on your head, then I noticed that your hairdo could have been a very pleasant support of a composition showing the kangaroo’s ears sticking out from your sunglasses. It was one of those special moments when everything came together in my eyes and I could see the final result before releasing the shutter.”

When Mr. Zucchi asked me to take the picture he had me crouch a little bit so I would align better with the kangaroo’s ears. He also had me push my sunglasses farther back on my head. I was not standing near the kangaroo at the time so Mr. Zucchi saw the image and me separately and thought we would go well together. It fascinates me that he could pick me out from across the room and picture me so seamlessly with the kangaroo. I think that there would be less of an artistic quality to Mr. Zucchi’s work if they were mere accidents. I also think that they would be less artistic if he brought models into a gallery to fit with a piece of art. Mr. Zucchi finds the perfect balance between having a “photographer’s eye” and constructing an image.

Why did you start taking this style of photograph?

“For more than 25 years my wife has been an Italian foreign language docent at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Very often I would drive her there for her tours. Having to spend several hours at the Gallery, I used to take my camera with me. Little by little I started taking photographs of museum visitors, without having any idea of exactly what I was looking for. Perhaps I was inspired by the photography of Thomas Struth.

When, by pure chance, I took a couple of photographs of visitors in front of a painting, and I realized that the combination of the visitor’s image with the art could create a surprising, different and pleasant picture, I decided to pursue that idea further.”

I like that Mr. Zucchi was inspired by his own work and experimentation. His works convey a sense of spontaneity at the same time they show years of experience. I find irony in the Thomas Struth inspiration because both Mr. Zucchi and Struth take pictures of the same thing, but in opposite ways. Struth focuses on the reaction of people where Mr. Zucchi eliminates the human face from all of his pictures. Yet, they both focus on the human interaction with art.

Do you see a picture and try to find a matching person or do you find a person and try to find an image or do you see it all at once?

“Both. When I visit a new museum exhibition, I first inspect it and try to identify the pieces of art, regardless of their actual artistic value, that I think are most suitable for my purpose. Then I look around for visitors that, for their clothing, hair, or some special aspect, could somehow combine with the art in creating a new image. Sometimes the look of the visitor guides me to a specific work, at other times the art makes me chose among the visitors.”

How often do people decline your offer to take photographs of them?

“Very seldom. Maybe because the first thing I say when approaching a visitor is ‘I’m not going to take a picture of your face’, or perhaps because my obvious age makes me look not particularly threatening. Usually I find that people react to my request of collaboration with surprise, curiosity, interest, and fun. That makes my experience even more pleasant. In the few instances when the person that I approach shows signs of uneasiness and declines my request, I do not insist. I’m convinced that it should be a pleasant experience not only for me but for everybody involved.”

True. Mr. Zucchi gave off a pleasant, grandfatherly vibe in a way that made him almost impossible to decline.

How many of the pictures that you take would you consider successful?

“It depends. During the long hours that I spend in a museum when I go ‘hunting,’ I try to get as many images as I can, even though many times they turn out to be uninteresting. Under normal circumstances I end up with maybe 15/20 basic compositions in one day. Of each one of those, I take several shots with minimal variations, in order to increase the chances to get the ‘right one.’ In total, I’d say that on a good day I could count between 100 and 150 shots. Out of which, if my curator selects more than 5 images, I consider it a very successful expedition.”

Again, Mr. Zucchi achieves a balance of a concept that we have talked about in our photography class, the planned image versus the machine gun approach. He takes several quick shots of one image from slightly different angles that he has pre-visualized.

How do you pick where you are going to photograph?

“I look for places where there are exhibitions featuring art that I consider promising for my purposes and that I have never ‘used’ before, and where I anticipate there will be a large number of visitors. I consider the Museum of Modern Art in New York to be by far the best place for my purposes. I also like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Virginia Museum of Fine Art in Richmond and the Art Institute of Chicago. In Washington, I like the East Building of the National Gallery of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Phillips Collection, the Hirshhorn Museum, and the now defunct Corcoran Gallery of Art. Only recently I discovered the photo exhibitions at the National Museum of Natural History--the subjects, sizes, and colors of those photographs have been an extraordinary, exciting opportunity to diversify my interests.”

Mr. Zucchi’s willingness to talk to me about his artistic process introduced me to a new way of looking at art in a gallery. I generally prefer going to a museum or gallery when it is empty. Mr. Zucchi disagrees. From now on, instead of feeling annoyed and agitated in a crowded museum, I hope to start looking for visual games to play with the art and the people. I appreciate the conversation I had with Mr. Zucchi and the follow up emails because it gave me a unique opportunity to think about the way people look at art and experience a gallery. He forced me to explore the idea that there are other reasons to go to a gallery besides simply viewing the art.